Supporting local governments to embrace complexity and learning in Eastern Partnership for better decision-making and scaling

Written by Beatriz Cano Buchholz Programme Manager, CPI Europe, Tina Saeteraas Stoum, Regional Orchestrator, UNDP IRH, Aditi Soni Service Designer, UNDP IRH, Akshay AgarwalSenior Associate, CPI Asia

Lessons from the joint EU & UNDP initiative Mayors for Economic Growth

“What was interesting is that we’ve changed our initial plan along the program based on what we heard during interviews with residents. We started this process with a very narrow angle and a clear idea of what the solution would be, but with your recommendation we opened up our view to listen better, and ensure we incorporate a wide diversity of views from visitors. It’s not about what we want, it’s about what they want,” said Samtredia team member

Today’s uncertain, globalized and interconnected world requires governments to embrace the challenges we face in all their complexity. In parallel, trust in governments has decreased over the years, highlighting the need to work towards strengthening relationships with citizens and reimagining the role of governments.

Leading in complex environments requires governments to move away from linear thinking to adopt new approaches that enables them acknowledge the importance of the system around the problem, design solutions that meet evolving community needs and embrace an experimental, iterative mindset to day- to-day activities. Leading in complexity requires a willingness to embrace failure and a recognition that there will always be opportunities to adapt and improve. In short, it requires a change of mindsets to embrace a culture that encourages to learn from failure and asks how we can better orient services, organisations, and systems to meet peoples’ needs and be continuously learning. One approach that can facilitte this transition and is rapidly expanding in the public sector is design thinking. Design thinking is a creative problem-solving approach that seeks to design solutions to existing challenges by closely involving end-users in the process, and using experimentation to help governments create more impactful solutions.

At the start of 2022, the European Union (EU), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Centre for Public Impact (CPI) launched a programme to support local governments to apply complexity-informed approaches to their most pressing urban challenges.

Urban Imaginaries was designed as a ten-month learning journey to strengthen the innovation capabilities of mayors and city leaders in nine cities across Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova, equipping them with the skills needed to take a holistic and experimental approach to develop solutions to challenges. In practice, we collectively designed a journey that kept design thinking/human centred design at its core to train and guide selected municipalities in tackling local development challenges.

The EU, UNDP and CPI delivered the programme through workshops, mentorship inspirational talks and regular cohort learning sessions. We also exposed cities to approaches and frameworks such as future foresight, systems thinking, storytelling for systems change and Human earning Systems (HLS). All of this was aimed at encouraging them to look at their urban environment through different perspectives, and building excitement for being bold, and doing things differently as they reimagine public services and spaces.

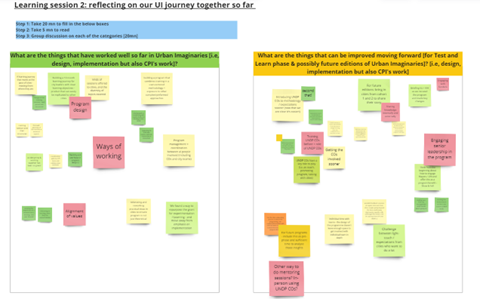

As we’ve wrapped up our journey with the first cohort, we wanted to reflect on what we have learned along the way:

1. Supporting governments to embrace complexity requires meeting people where they are and going beyond the “one size fits all” approach.

Embracing complexity and systems thinking in government requires public officials to think, act and relate differently. This means governments must view themselves and their role differently – moving away from the expert to the humble mindset. But they must also reimagine how they design public spaces and services, by embracing methods anchored in experimentation, learning and iteration.

In Urban Imaginaries, we used design thinking as the core approach to introduce city teams to concepts such as deep listening, complexity, systems thinking and experimentation. We adapted to this approach to take into account the starting point of teams. Meeting people where they are is important – most had never heard of design thinking before.

Creative tools, such as using a Miro board, can help teams step outside their comfort zones and visually map out their challenge.

The journey kicked off with a deep listening process. We invited teams to conduct a series of conversations with residents, business partners, and NGOs to better understand how people were experiencing their challenge. This also helped the teams realise the value of engaging with residents.

“What I liked from conversations with residents is that residents value us engaging with them. We’ve learnt that it is important to engage all citizens of Cahul municipality, as they can become part of the problem-solving to transform our cities into a better place.” (Cahul team, Moldova)

“The joint involvement of the civil society together with the public administration brings the most sustainable results.” (Calarasi team, Moldova)

As we progressed, teams were introduced to experimentation, designing and testing experiments to build solutions to their identified challenges. A big takeaway for teams here was realizing the value of designing with stakeholders instead of designing for.

“What surprised us? How active people were to share feedback. We learnt engagement with residents helps us to make the correct decisions & this is what we realised in the course of this process / training. People came up with their ideas, and we learnt a lot. There were so many ideas that we had never thought about! It was so helpful to really ASK people what they need from the city hall to embrace a healthier lifestyle?” (Samtredia team, Georgia).

In parallel, this has also raised questions about the role of governments. Teams have started to perceive themselves as system stewards responsible for identifying the value of each partner and connecting actors: “In Rustavi, we’re working to support the creation of a hub for young people to receive training in digital skills. Through deep listening, we’ve realized that local youth organizations have been doing this for a long time. Our role as government is to amplify the work of other organizations.” (Rustavi team, Georgia)

2. Supporting change in government? Look out for the small things and recognize that learning is layered and spreads across various part of the process.

Change in government is hard. And it takes time! Why? Because change does not refer to changing how things are done but how people think. Change in governments means transforming the habits and mindsets that define how governments work today. Real change isn’t about just doing things differently; as Adrian Brown from CPI put it, it’s about a new way of being.

In Urban Imaginaries, we began with the assumption that introducing complexity-informed approaches to public servants can support the change we seek by reinventing government practice around people and systems. By learning to do things differently, government officials enter a journey of individual learning and reinvention which ultimately leads to a paradigm shift in how governments think and approach complex problems around them.

We recognise how hard it is to document the individual change happening, and we continue exploring how to do this better. Yet, reflections from cities provide early signs of transformation.

In Poti, for example, the team reflected on the value of experimentation in government, and how it can support teams to design public spaces and services more intentionally.

“Prototype is crucial – it helps to improve any project to make it more tailored to people’s needs. We had different ideas at the beginning, but we then moved to different ideas based on what we heard from residents. This experiment made a real influence! People came, and it gave another life to the park. People became more active and fuller of initiatives – they are now suggesting what they hope to see, what we can improve etc. Previously, they did not have any initiative to share with us suggestions – they now do!” (Poti team, Georgia).

Along the journey, teams also built behaviours crucial in building trust and legitimacy in government: authenticity, humility, and not being afraid to be challenged. The Samtredia team quickly changed their initial ideas for promoting a more healthy lifestyle in the city, realising they were not the experts in the room.

“Interviews revealed some needs and interesting insights. What was interesting is that we’ve changed our initial plan based on the insights collected. We started this process with a very narrow angle, but with your recommendation we opened up our view to capture better a diversity of views from the visitors. It’s not about what we want, it’s about what they want.” (Samtredia team, Georgia)

“I am surprised at the results of the interviews! It seems the residents are really keen to get involved and they have a MUCH bigger understanding of the issue.” (Alaverdi team, Armenia)

3. Collaborate internally to understand the system, design an experience relevant to the municipalities and eliminate obstacles to experimentation

As we started designing Urban Imaginaries, M4EG and CPI teams spent a considerable amount of time to better understand the programme needs, the geopolitical context, the partners and our collective vision. In other words – understanding better our very own Urban Imaginaries system, and mapping out the actors and relationships that link them.

Among others, we reflected on our vision for this program together, and asked ourselves – What change are we seeking to support? We considered what dynamics and hidden pressures might affect the work. What is the level of innovation in the participating cities? Are there any local political tensions that might impact the delivery of the programme? How can we distribute funds to cities? Who do we need to report to, and how? We also thought about the expectations of all who involved into the process. What does success look like for each of us?

Working with partners in such a collaborative, humble and open way has allowed us to build a narrative for the programme jointly. It’s also enabled us to experiment as we go – iterating when needed, something UNDP is currently exploring.

For instance, one of the changes we’ve made to the programme was understanding that we needed to create a safe space for cities to experiment – and learn. We sought to create these conditions by delivering the grant of EUR 60,000 in the middle of the programme so cities could use these funds to design and test experiments. While some cities preferred to use funds for implementation instead, this small change signalled the importance of experimentation, removing the risks associated with it and highlighting and emphasizing on learning as the overarching goal of our programme.

4. Embracing a learning mindset and designing a programme structure to engage in learning by doing [Text Wrapping Break]

One of the main objectives of Urban Imaginaries was to support city teams to learn – and understand the central role of learning in the journey of accelerating change in government. To support this, our team facilitated regular cohort-based learning sessions for cities to get together and share their experiences and reflections on what they were learning as they experimented with doing things differently.

A powerful learning for us was the importance of learning by doing. Trying out the approach and tools in practice is critical to facilitating the adoption of new approaches in governments, and for public officials to gain trust in these practices and behaviours. Participants must engage closely with the problem-solving process in a practical, hands-on way to experiment at the individual level, and “test and learn” to enable change in their mindsets.

What we’re still wondering:

Reflections mentioned above are just the beginning of our learning journey, and there are several things we’re still wondering about:

- How can we better support long lasting adoption of complexity informed approaches within the wider ecosystem? Sustainable change takes time and should not be siloed. How can we empower teams to amplify the adoption of complexity-informed approaches to the wider organisation? How can we ensure this change will last in time? How can we push them to be ambitious and think of ways to transform the broader system?

- How can we best tell the city’s story of change? As John Burgoyne has written, “Measurement should not be used for top-down control, but rather to learn about complex problems and the people experiencing them, so we can adapt and improve our approach.” While we used storytelling throughout the program and invited cities to share their experiences through regular internal Show & Tells, there is room for reimagining how we define impact. As we continue our journey, how can we best document and illustrate the change that is happening in cities and use storytelling as a tool to showcase impact and learning?

Looking ahead

Throughout this programme, we have seen the importance of embracing complexity, supporting change at an individual level, the benefits of working together with partners and the value of a learning mindset. As we embark on 2023, we will keep on collaborating to uncover some more answers.

We’re continuing the Urban Imaginaries programme supporting a second cohort of nine cities from Azerbaijan and Ukraine. We’re working with Azerbaijan cities in a variety of topics spamming from designing a pilot program to support the reinsertion of incarcerated women in society and supporting the development of a gastronomy tourism destination. In Ukraine, we are supporting cities to engage residents in reimagining the cities of tomorrow, in particular as they look at building forward better. We look forward to sharing our insights as we continue our work to help shape the cities of the future.

Learn more about the cities learning journeys:

- Armenian communities test human-centered design for improved service delivery under the M4EG [January 2023]

- Can urban waste be reimagined? The journey of Calarasi, Moldova [July 2022]

- How cities are engaging with residents to imagine the cities of tomorrow [October 2022]

- Learnings from Urban Imaginaries – Georgia [April 2023]

Disclaimer:

This publication was funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the Mayors for Economic Growth Facility and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

The M4EG Facility draws on the Mayors for Economic Growth Initiative, launched and funded by the European Union (EU) in 2017. Since 2021, the EU-funded M4EG Facility has been managed by UNDP in close cooperation with the EU, local authorities, and a range of partners.